Four Surprising Ways You Are Biasing Your Data

/How much did you spend on market research last year?

If you are like most companies, you are making a big investment on market research hoping to gain insights. And these data are used to make very important decisions in various areas, from product development to customer segmentation, or from marketing campaigns to product strategy.

But how can you be positive you are relying on accurate and unbiased data?

In the recent years, the field of behavioral science such as behavioral economics and decision making research are discovering that data can be easily biased based on very subtle cues, such as wording of questions or the order of questions. We’ve been also learning that people (including your customers and ourselves) are not always rational and therefore, we provide inconsistent responses based on the environment or the state we are in.

The implications for researchers, though, haven’t been well documented.

In order to avoid collecting biased data, and hence relying on inaccurate data, what do you need to do?

The first step is to understand how your consumers really make decisions.

For example, do your consumers tend to make decisions mostly based on fast thinking (e.g., intuition, gut feeling, “what feels right”) vs. slow thinking (e.g., deep/elaborative thinking that requires weighs pros and cons from all the alternatives available to you)? I cannot tell you the answer without knowing your customers and your products/services. But I can tell you that they are relying more on intuition than you might think – or you might want to believe.

In fact, some behavioral researchers including myself believe that 75-85% of decisions we make are mostly based on intuition and not based on slow thinking.

That is because we simply do not have enough resources, such as time, energy, cognitive resources, and willpower to make all the decisions based on slow thinking. For example, how did you decide what to have for breakfast? Did you weighs pros and cons of all the possible options from your pantry and decide which one to have? The answer most likely is no. You grabbed whatever that comes to your mind first.

But wait, you might say, I know most people don’t think much before they decide what they’d have for breakfast but our customers do when it comes to our products. After all, your customers in your focus groups tell you all the reasons why they chose (or didn’t choose) your products over your competitors. Isn’t that evidence that they are thinking when they are deciding?

Or you might say that your products require careful thinking because your products come with consequences, such as financial and health/medical services.

Decades of research in behavioral science tells you otherwise.

Here is some evidence that people do not put too much thoughts into deciding or do not have strong preference. And therefore, seemingly irrelevant factors affect our behaviors and in turn lead to irrational behavior:

1. Anchoring effect

Anchoring effect occurs when previously exposed information influence subsequent evaluations.

In one academic study, a group of research participants were presented with the information about various consumer products (e.g., wine, chocolate truffles, a book) and were asked whether or not they would purchase those items for the price of the last two digits of their Social Security number. For example, your last two digits of Social Security number were 25, then you’ll be asked whether or not you’d purchase the bottle of wine for $25. Then they were asked the maximum amount of money they’d be willing to pay to purchase the bottle of wine.

The researchers found that the maximum amount of money participants would pay was significantly correlated with the last two digits of their social security number. The price they were willing to pay for a box of chocolate truffles were especially susceptible to anchoring effect: participants with the very low digits (e.g., 12) were willing to pay $35.90 but participants with very high digits (e.g., 85) of Social Security number were willing to pay $79.80. That's more than twice as much as those with the low digits!

This surprising results is because participants used (e.g., anchored to) the last two digits of Social Security numbers in coming up with the maximum amount they’d be willing to pay.

There are several implications for marketing researchers. One is that we need to be mindful of question order. Is the previous question/answer serving as an anchoring point? How about the choice order? Is it possible that the first option is serving as an anchoring point for the second option? How about the participants ID they might be assigned? In order to avoid anchoring effect, we may consider randomizing not only the option order but also the question order. It may also necessary to remove some numeric information that may be serving as an anchoring point.

2. The power of default

Whether or not you should be an organ donor seems to be a substantial decision. It affects what could happen after your death. It could also affect your family and friends significantly as well. So, would you say people are very rational when it comes to deciding to or not to be an organ donor? That is, people would spend sufficient amount of resources on this decision and have a consistent preference.

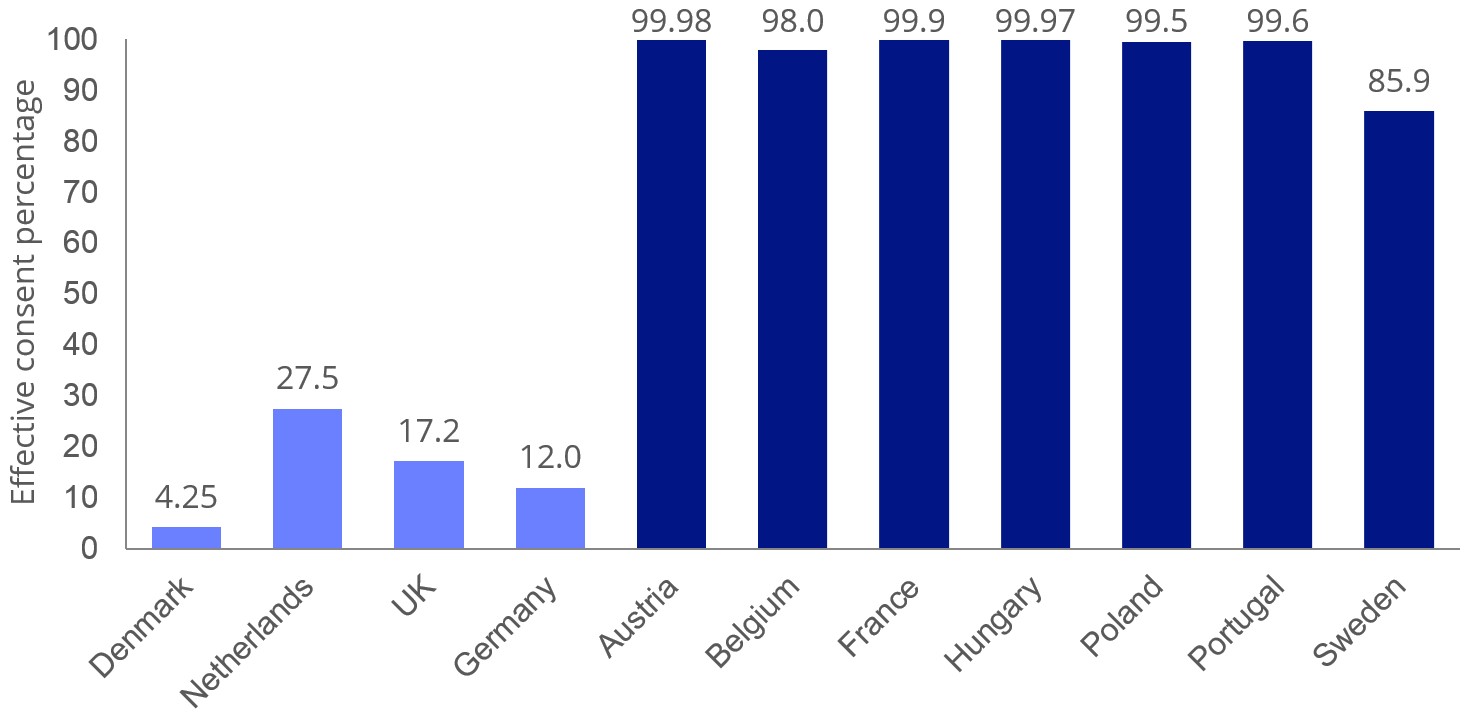

The graph below is suggesting they are not.

As you quickly notice, in the countries shown with light blue bars (e.g., Demark, Netherlands, UK and Germany) have only a very small percentage of people who are organ donors. In the countries with dark blue bars, a very high percentage are donors.

So, this means that people represented in the light blue bar didn't want to be an organ donor right?

Not necessarily.

It turned out that the difference between these light-blue countries and dark-blue countries is very simple: the default. In the light-blue countries, people need to opt in to be an organ donor. That is, you are not an organ donor by default. In the dark-blue countries, people are by default an organ donor, and you’ll need to opt out if you don’t want to be an organ donor.

This, along with many other studies that have been done on the effect of the default, demonstrate that people’s responses can be easily influenced by a default, even around very consequential decisions. As a researcher, it is important to avoid accidentally encouraging your participants to choose one option because it’s what they think is default.

3. Framing effects

I describe framing effect more in depth in another blog post (see my blog post on framing here) I made earlier but the framing effect essentially is that a particular mental frame people use to interpret information can lead to different evaluations and decisions. That is, how you frame or word information can lead people to focus on different aspects of the same information, and in turn lead to different preferences or choices.

For example, describing a pasta sauce as 15% meat leads to more favorable evaluation of the product than describing the same pasta sauce as 85% tomato sauce.

And interestingly, describing a separate pasta sauce as 5% meat leads to more unfavorable evaluation of the product than describing the same pasta sauce as 95% tomato sauce.

Framing effects illustrate that people’s evaluations and choices are very susceptible to subtle difference in wording. You’d need to be careful how you frame your product information, how you frame your questions, and how you frame your choice options. In order to avoid framing effect, you may consider splitting your participants into 2 groups, and use one framing in one group, and another framing in another group. Then see if there's any significant difference. If there is, it indicates that participants are susceptible to framing effect. If not, framing has a minimal effect in the particular question.

4. Asymmetrical dominance effect

A team of researchers were interested in the effect of a price and quality on beer choice. Here is the information:

|

Brand A: $1.80 and quality rating of 50 out of 100 Brand B: $2.60 and quality rating of 70 out of 100 |

The majority (67%) of people chose Brand B. So, you might conclude that people prefer Brand B to Brand A?

Let’s look at another set of data, collected by the same team of researchers.

As you see below, Brand A and B are still there but they also added Brand C.

|

Brand A: $1.80 and quality rating of 50 out of 100 Brand B: $2.60 and quality rating of 70 out of 100 Brand C: $1.80 and quality rating of 40 out of 100 |

The results: virtually nobody chose the new option (e.g., Brand C) but the majority (63%) of people chose Brand A.

What happened here? Brand A and B are identical in the first and the second group, and nobody chose Brand C. So it’s not like those who were choosing Brand B shifted to Brand C. Instead, those who were choosing Brand B in the first group now shifted to Brand A even though the information about these two brands have not changed at all!

The reason most people now chose Brand A is because it looks much better compared to Brand C (e.g., in academic research, we call these unpopular options a decoy option).

The implication here is that you will need to be careful with what options you present together to your participants. You might be inadvertently highlighting certain aspects of products by providing a comparison or a reference point. Consider asking about one product at a time. Or consider grouping different products for different participants and see if there's any significant difference between the groups.

The studies I described above demonstrate that we are affected by seemingly irrelevant factors. And this in turn leads us to be inconsistent and irrational. It is because we often make decisions without putting too much thought into them and instead, rely on information that easily comes to our mind.

But we don’t like to admit that.

So, when asked, we often make up the reason as to why we did what we did. So if you ask the participants who chose the beer from Brand B in the first set about their decisions, then they might tell you that the beer quality is very important for them and that the price is secondary. But we now know that this is not necessarily true. Because if it was, it shouldn’t matter whether they were presented with Brand C or not! So, more often than not, the reasons your consumers tell you regrading what they did are constructed to be consistent with what they already did. This is because they want to present themselves as a thoughtful person rather than somebody who acts with little thinking.

But why do we like to believe that we are rational and rely more on slow thinking?

Well, because that’s the virtue in our society, and we all want to shed ourselves in a positive light. Note that there’s nothing wrong with it. However, this presents researchers with significant challenges in understanding customer behaviors.

So, what can we do to make sure we are not getting biased data?

Be mindful of these 4 common biases in each questions you have in your research projects. Carefully consider how your research may be (consciously or unconsciously) affecting your participants' responses. Consider alternate way of asking the same questions. In addition, explore if randomized controlled test (e.g., experiments) is right for you (click here for HBR article). This may be the only way to truly test if there's any biases.

If you'd like to learn more about the specific applications of behavioral economics in your next research projects, we are offering online course (PRC) on behavioral economics for market researchers in April 2016 (partnering with Research Rockstar), click here to sign up!

Contact us if you'd like to see how we can help you, too. We leverage 15 years of extensive experience in decision-making research and behavioral economics to help our clients better understand, predict and ultimately influence their customer behaviors. Contact us here or at namika@sagaraconsulting.com.

References:

Johnson, Eric J., and Daniel Goldstein. "Do defaults save lives?" Science (New York, NY) 302.5649 (2003): 1338.

Janiszewski, Chris, Tim Silk, and Alan DJ Cooke. "Different scales for different frames: The role of subjective scales and experience in explaining attribute-framing effects." Journal of Consumer Research 30.3 (2003): 311-325.)

Huber, Joel, John W. Payne, and Christopher Puto. "Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: Violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis."Journal of consumer research (1982): 90-98.

Bergman, Oscar, et al. "Anchoring and cognitive ability." Economics Letters107.1 (2010): 66-68.